A Chat With: Julia Armfield

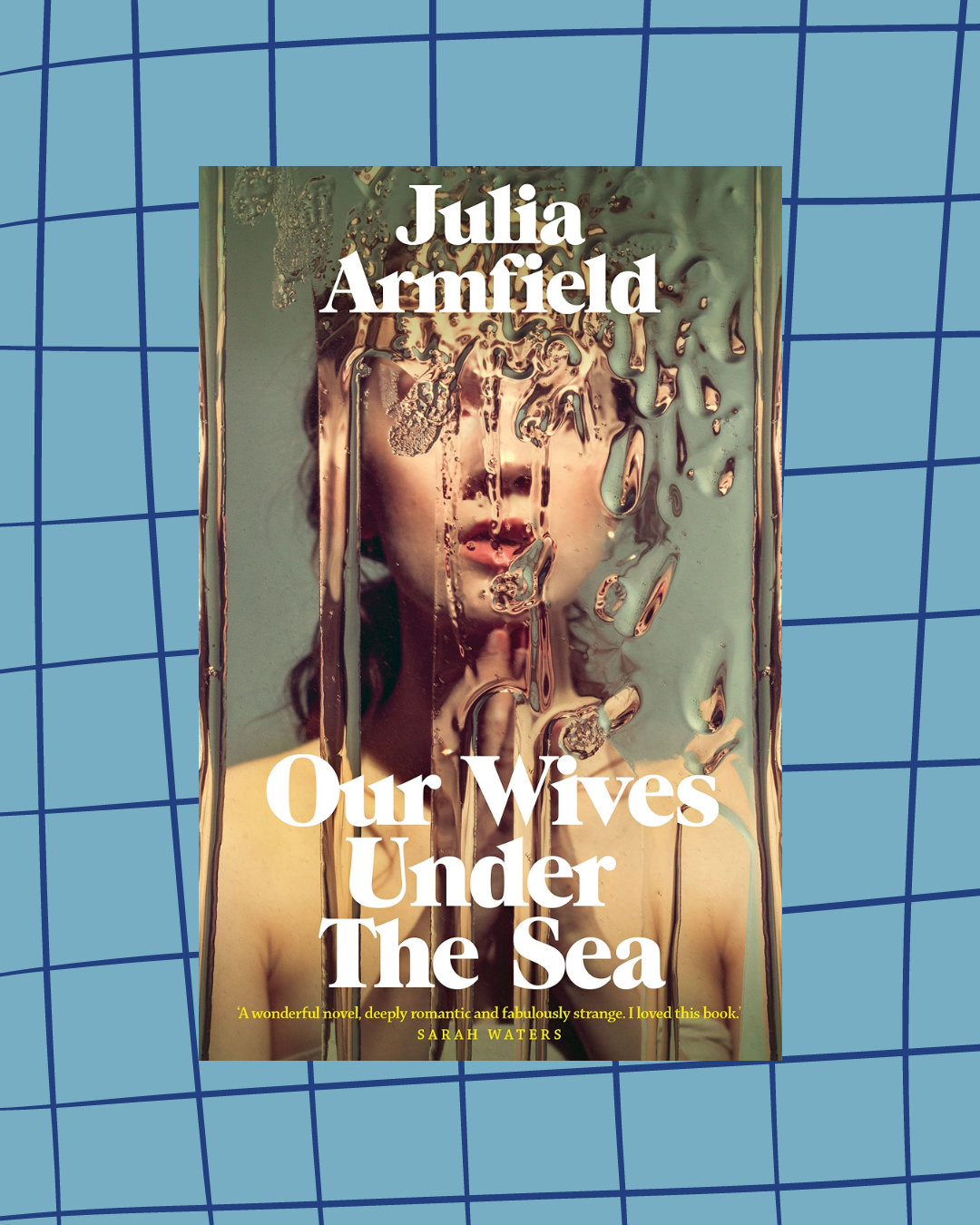

Julia Armfield was born in London in 1990. She is a fiction writer and occasional playwright with a Master’s in Victorian Art and Literature from Royal Holloway University. She was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year in 2019. She was commended in the Moth Short Story Prize 2017, longlisted for the Deborah Rogers Award 2018, and won the White Review Short Story Prize 2018. Her first book, Salt Slow, is a collection of short stories about bodies and the bodily, mapping the skin and bones of its characters through their experiences of isolation, obsession and love. She won the Pushcart Prize in 2020. Our Wives Under the Sea is Julia’s debut novel and is shortlisted for the 2023 Nota Bene Prize.

So, for those who haven't read Our Wives Under the Sea, do you think you could give a little synopsis?

Our Wives Under the Sea is a novel about a marriage, but it's also a novel about the deep, deep sea. Miri and Leah are a married couple, and Leah is a marine biologist and researcher who has gone on a deep-sea mission which has clearly gone extremely wrong and lasted too long. The novel moves back and forth between both of their perspectives, both in the timeline where Leah is at the bottom of the sea and then afterwards when she has come back, clearly quite changed, and Miri is trying to deal with that.

Thank you. I was wondering what inspires your powerful imagery of water and the ocean and what it is about the sea that draws you in, both in your short story collection and your novel?

I think that I've always been more writing-based than plot-based if that makes sense, and when you write something that is about such a central image - the ocean is so key, both to the Leah section but also to the Miri section - I think you feel like to do that image justice you really need to bed down into it and figure out how it actually affects everything else that you're writing about.

The imagery of the ocean and the water is useful as a way of invoking liminality and change, and the idea of something being on the surface and another thing being underneath the surface, which I think is quite key to more general points in the book. And I've written about this before, but I'm very interested in images of water and the ocean as they pertain to queer women's literature and film quite specifically. I think that there is a lot there - a lot of things which you could put within ‘the canon’ - that are often to do with the sea. You have things like Portrait of a Lady on Fire; a lot of Sarah Waters’ novels which kind of randomly take place by the sea; really terrible things like that Channel 4 show Sugar Rush from years ago. There’s this idea of danger and change and unreliability, and the idea of something, again, being potentially very calm on the surface and another thing underneath. I was interested in the kind of tension between those two things, and how I could invoke that when writing about the ocean.

I also think it’s a symbol of fear, but also of romance as well, and maybe that's why it works, because fear and romance go hand-in-hand.

Yeah, fear and romance are the same thing in a way. I often say that horror and romance are essentially the same genre because they spring from the same fear. They spring from fear of death and fear of loss and fear of throwing oneself fully into one thing.

That's really interesting. You have just briefly touched on this, but I read somewhere that you're much more inspired by movies than books, so which films informed Our Wives, which does feel like quite a cinematic book?

I think that I definitely am. I fully can read, but at the same time, I think that whenever I want to be inspired by something, it usually appears to me from movies first because most of my writing usually comes from picturing a scene, or a tone, or light through a window, and then building out from there, and so I think it comes from imagining a scene in a movie. Movie-wise I was very inspired by - not necessarily beautiful, romantic movies - but by the abyss. I am a big lover of shark movies as well, so obviously Jaws turns up a lot in the book, and also, just dramatically, quite a lot of horror movies. I was very inspired by both Suspirias, the original Suspiria and the Luca Guadagnino remake of Suspiria, because they're about bodies and unreliability and they're also just about the consciousness of a horrible change in one's body, and I'm really interested in stuff like that. I think horror movies are so often the perfect medium for very, very powerful imagery because they are so visual.

What did you want to explore through bodily transformation in the book?

I'm always interested in the osmosis of people and the fact that bodies are changing, being embodied is changing constantly, and the unreliability of oneself is kind of the key thing that makes you a person. I wrote an essay a little while ago about a hospital experience that I had, and I think it's something Hillary Mantel said along the lines of, ‘Having a body is being trapped in a battle that you will eventually lose’. Even if nothing happens to your whole entire life, even if you are incredibly fortunate, you are eventually going to get old, and you are going to die, and the consciousness of that is something that I find fascinating. It was something I basically said in the essay, which was that watching a horror movie is knowing that something is going to happen at some point, and having a body is kind of the same thing. I wanted to think about that in a sort of sped-up way in this novel.

I've found myself thinking of so many different things that Leah's transformation could represent, so as well as a physical illness, it could be PTSD or depression, or even just a metaphorical manifestation of a couple growing apart. But I wondered if horror and the absurd are always metaphorical for you on some level?

I think they can be, and I think that as a writer, you need to know deep down what your intention actually is, even if you keep everything ambiguous because I think that otherwise, you really run the risk of contradicting yourself. But I think that horror and metaphor and the absurd and all of that are basically the perfect conduits to talking about a lot of things at once, because we all experience our extremely mundane lives with aspects of horror and aspects of the absurd at all times, and so, I think it's just like turning up a knob on one thing. Edging into genre and edging into horror means that you don't necessarily need to speak your point aloud because it's more about the way that people experience things rather than necessarily the thing they experience.

And every reader's going to interpret it differently and bring whatever they see to the story.

Exactly. I don’t think that all writers feel this, but my perspective has always been that the second that it's finished and it's published, it's no longer my business. It's not my business to dictate how anybody takes it, because I don't think it belongs to me anymore. Particularly, I think that people should be able to take their own interpretations away from things.

Completely, and maybe it's a bit of a relief approaching it like that; you don't then have to fight your battle of how people interact with it – you can let it go.

So I kind of thought that Miri seems quite unwilling to tackle head on the situation with Leah and she doesn't really confess to others what's going on. She sort of just loses herself in the memories of their relationship rather than focusing on what Leah's actually experiencing. Her loss is kind of subtle and slow and mixed up in memory and self. Do you think Miri senses an inevitability to her loss and a sort of reluctance and avoidance to deal with the full picture of her grief?

I think that's a really nice way of putting It. There's quite a lot that was going through my mind about Miri as a hypochondriac specifically in the novel. As a hypochondriac, whilst you're spending all of your time expecting the worst, there is a little part of your brain that also thinks that actually, you know this isn't true because you know that you're a hypochondriac and that actually, you’ll be proved wrong. Miri is always, on the one hand, absolutely expecting the worst thing to happen, but at the same time potentially thinking, ‘Yes, but maybe I've made this up the way that I make up everything that's happening to me’. And so, you're stuck between two poles of absolutely knowing that something is grindingly going to happen to you, and at the same time, relying on a reprieve that is not actually coming. So, I think it was about the tension between those two things of just absolutely being aware of a decline and not really wanting to deal with it, and at the same time, thinking, ‘Yes, maybe not, maybe not at all’. I think so much of the novel, for me - just in the structure as well - is about the way people consistently pull in two directions, going both up and down at all times. You have the two voices, you have the submarine going down and the submarine coming up, and I think that was basically what I wanted to be going on with everybody's experiences to some degree. Kind of hoping for something and knowing something else was happening at the same time, do you know what I mean?

Yes, I do, and you see that in the section where Miri is on the online forum about grief and hope and how it's really hard to exist between both of those things.

Because one kind of stops you from fully leaning into the other thing, and so eventually you have to pick one. Yeah, I think that's a really good way of putting it.

And a random sidenote, but I also considered Leah at one point as an extension of Miri’s own hypochondria - her obsession with the physical and the body and the body's deterioration materialised.

Yeah, definitely. And the strangeness of having essentially manifested that, but for someone else rather than for herself, because I think there's a lot of guilt in Miri as well. So much of the book is also to do with something having happened to her mother at some point, and about grief, or not having grieved well, and kind of getting a chance to do it better this time. I think grief is so fundamentally selfish because you're not grieving for the person, you're grieving for yourself without the person, or the anticipation of yourself without the person. And so, I think a lot of it was about that as well.

With the epigraph from Moby Dick and this idea of the ‘half-known life’, I was interested in this idea applied to Miri and Leah's relationship, to the sunken things they don't know about one another. How did you think of the half-known life on a personal level for the characters?

It's a very boring answer, but I don't know how well we ever know the people that are the closest to us, and how often one is forced into closer proximity with people only at times of crisis and at times of anticipated grief. It was interesting to me the way that you can love a person so completely, but also be so closed out of their passions and the things that are actually kind of key to their lives. Miri is one entire aspect of Leah's life, but Leah has an entire other place and an entire other thing that’s completely away from her. And whilst Our Wives Under The Sea is obviously an extremely extreme example, I don't think that it's necessarily rare; I think that a person can be absolutely everything to you and at the same time be on some level completely unknown to you. And so, I think I'm always interested in that kind of thing. I'm interested in extremely mundane things about relationships and about people, but kind of refracted through a genre lens.

I think that’s what you’ve captured so well, the small moments that make up love and relationships and that are for other people, quite boring, but are really romantic for the people inside them.

Yeah, exactly. Because everything is monumental in love in some way, isn't it? And everything is genre in love, in a way; everything is horror or action or any of those things, while being quite mundane at the same time.

So how did you progress from writing short stories to a novel? How did you find the story that you wanted to take further?

So what happened was that I had a short story collection, and absolutely 99% of the time, if you have a short story collection that somebody wants to publish, they’ll say, ‘That's cute, but do have a novel as well?’ And so that is just what happened. I was contracted for a short story collection and a novel, and I had a pitch for a novel, which I basically just made-up on the hoof. I absolutely did not end up writing that novel; I did write a different novel which then did not get published. And my editor, who has always been wonderful, was like, ‘I appreciate so much about this, but I don't think it is the right thing for us to publish’. And my partner, because she's extremely sensible, said, ‘Okay, why don't you take a month and figure out what it is you want to write instead?’ And I, because I'm not sensible, started writing Our Wives that day. Our Wives Under The Sea had actually been a short story that I had wanted to write as a present to myself for finishing the novel that then got rejected, and I was extremely fortunate about that because it was originally a short story that was going to be from Miri’s perspective. It was much more about the unknown, about someone having come back from something, and about how little of a person, the person that you love most, you can recognise, and that wouldn't have worked as a novel. And I realised that if I split the perspectives - because it was such a static story in so many ways and because it's a static novel in a lot of ways, it's about being trapped in one place and being trapped in another place - I could keep the movements and I could have them in conversation even though nothing was actually moving very much within the text most of the time, and so I built it out from there. I wrote it between March and December of 2020, so it was hard lockdown most of the time, which is an odd time to be writing a book, but then you look back afterwards and realise, ‘Oh, I wrote an isolation novel’.

You can see that in it.

The book is so much about being trapped in a flat and being trapped in a submarine and not going anywhere. And so yeah, it was more or less pure accident that I ended up writing this book. I'm so grateful for literally everybody - I'm so grateful for being told not to publish the other one because this was the right one. I had not written a novel before though, and I do genuinely think that everybody possibly needs to fail at least once with a novel before they can write one properly.

Does having the deadline help?

Yeah, I work so much better with deadlines. Being a certain type of exam kid at school makes me work much better to pressure. I know some people who are the complete opposite of that, but I don't need freedom.

I’m completely the same. So you have such a distinctive way of writing and voice and poetic turn of phrase, I wondered what writers inspire you the most?

That's a really good question, and there's a book that I return to an enormous amount called Geek Love by Katherine Dunn - it's very good, it's kind of a novel that you possibly couldn't and shouldn't write now; it's about a travelling carnival, written in the 1980s, and it is just astonishing. I've never read anything like it for turn of phrase or for plot development; there's something about the marrying together of the romantic and the grotesque which I don't think I've ever really seen in another novel done quite that way. And I read it kind of once every couple of years, and it makes me cry more each time, which I think must be adulthood in some way. It's horrible, but it's wonderful, and it's incredibly sad and incredibly weird. I also love - even though we have obviously nothing in common writing-wise – reading Joan Didion, or watching the Joan Didion documentary, when I need to literally just get going on a sentence level. Writing is all about rhythm for me, and there is something just so just so clean and perfectly placed about Didion’s writing at all times, which really, really gets my brain on the right track; if I'm out of rhythm, I can't write at all, and that's it. And sometimes The Shipping Crew by Annie Proux is one that I read a lot as well. It's almost over-descriptive for me now in a way that I didn't used to think it was, but there is something about her - particularly that she will never, ever use an expected word, and yet it's always the most perfect and precise word for something, and the most perfect, precise description. Even if a description is odd, I always want the description to bring me closer to an image not further away, and I always find that with her writing.

I think you do that really well too. Do you write poetry?

No, not at all. I'm not smart enough to write poetry and I'm not disciplined enough!

I'm sure that's not true! And lastly, huge congratulations for being shortlisted for the Nota Bene Prize, and because it’s a Prize all about word-of-mouth recommendations, what are the books that you love to recommend to people, that you think, ‘Oh everyone will like this’.

So probably not Geek Love because I don't think everybody would like it. An Australian writer called Jennifer Down, who I'm completely obsessed with. She's written two novels and a short story collection, all of which I just envy on every possible level: writing level, structure level, discipline level, everything. It's a novel called Our Magic Hour; a novel called Bodies of Light; and a short story collection called Pulse Points, and I would recommend those to everybody. And also, there is a New Zealand novel called Greta and Valdin which is coming out in the UK next year, and I love it. It just made me wish that I was funny and when I read it, for about 10 minutes I was funny when I was writing. But those are the books I would recommend.