A Chat With: Priscilla Morris

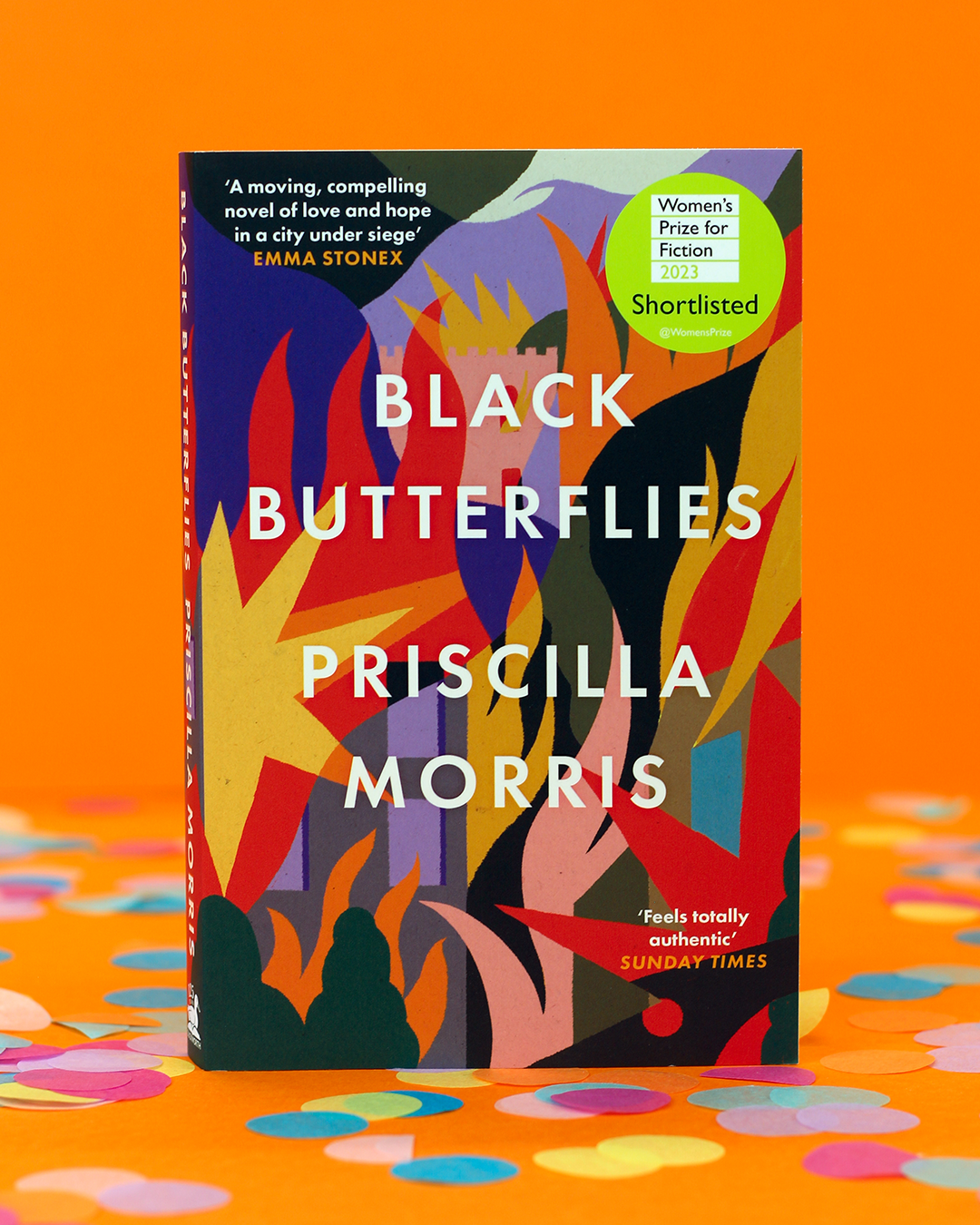

Our wonderful editorial partners, nb Magazine, sat down with the incredible Priscilla Morris to discuss her debut novel, Black Butterflies, which is shortlisted for the 2023 Nota Bene Prize. Their editor, Madeleine, speaks to Priscilla about her haunting yet hopeful book. Morris tells the story of the slow encroachment of violence on the historic and diverse city of Sarajevo from the perspective of the strong-willed and resolute artist, Zora. As the siege intensifies and the city's walls close in around Zora and her community, acts of resilience, resistance and resolution are expressed through art, companionship and the forces of common humanity that seek to triumph over conflict.

Thank you and welcome! Just to begin, I thought it would be useful if you could tell us a little bit more about what led you to the point of becoming a writer and now a debut author? How has the experience been for you?

I have wanted to be a writer since I was six years old; I just had an absolute love of reading and being read to; in particular, the wonderful stories of Roald Dahl, like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. For me, it was just the greatest pleasure to be in that world he was creating, and I just thought, if when I'm older I can be that voice in someone's head and give this experience to other people, that for me would be the greatest thing I could think of doing. So, that's where it started, and it has never left me.

It took me a long time to start writing fiction because I certainly had a lot of doubts about my ability to write and other conflicts, but I was writing diaries frantically from when I was ten years old, which really helped me learn my voice, I think. And then I started writing short stories at university, at Cambridge, and then I really got into the swing of writing in my early 30s. I moved to Brazil where I was teaching English; I spent three years in Rio which was beautiful. And there was something about the positive can-do attitude of the people that enabled me to lose my restraint; instead of asking myself ‘How dare I? I thought, ‘Just go for it’, and I started writing up to five hours a day and just loving the process without really thinking of an audience at that point.

I started writing this crazily long children's poem about the environment that was incredibly imaginative, and I loved doing it, but at one point I just looked at it and I thought, ‘What child is going to read this poem?’. So, at that stage I realized that I needed extra help and I applied to do a Master’s in creative writing at UEA when I was 35. That was the real turning point; that's when I got a lot of good feedback from my peers and met other writers, and that was when the inkling of the story for Black Butterflies first came to me, which is a story inspired by family history – my mother is from the former Yugoslavia, and I really wanted to try and understand the war in Sarajevo for myself.

Amazing. It might just be coincidence, but I've noticed an interest amongst authors I've spoken to recently in going back through their history to try to understand the experiences their family have endured. It seems that a lot of the younger generation are trying to do that work, and, in many cases, this discovery is expressed through writing in some way.

Very much so. And I very much enjoyed your previous issue on multi-generational literature, and I think this theory of inherited trauma is very useful. I’ve recently been reading a lot about that, and it makes a lot of sense to me; I think that's partly what I was doing in writing Black Butterflies, without realising it.

I actually just wanted to quickly ask you before we move on to talk about the book, just because you mentioned the fact that you lived in Brazil and you're now living between Ireland and Spain – do you think living in many countries and being exposed to different cultures has affected the way that you approach storytelling and writing?

Yes, yes, I do. I also lived in Barcelona and Italy when I was younger as my first degree at university was in languages – Spanish and Italian – so I also read a lot of Spanish, Italian, and South American literature – a lot of magical realism. This is a very different mode of storytelling to what perhaps we’re used to, which really gave me an appreciation for different forms of literature.

So, absolutely, I intentionally went and lived in other countries because I wanted to have something to embrace – different life experiences – and I wanted something to write about. I also studied Anthropology, which is very much about spotting patterns in life and how people do things differently in different cultures. And that fascinates me, no doubt because of my mother who’s very Yugoslav, and my father, who’s very English. So, trying to understand different ways of life has been part of me ever since I was very young, and being interested in different identities does absolutely feed into my writing.

Yes of course. Back to Black Butterflies, which is your wonderful debut set during the siege of Sarajevo; you've mentioned that the story is connected to your family although it is fictionalised, so when writing, you were having to imagine quite a harrowing experience occurring in a place that is quite close to you. I just wondered how that felt and how that affected you? And how did you begin that act of imagining?

Yes, it was tough. First of all, living through the actual thing was harrowing; the war started when I was 19 and went on for almost four years, and it was very upsetting at the time – seeing it every night on the news, people being shelled, people being shot by snipers as they crossed the street. Sarajevo became this real theatre of war, and everyone was watching it, but there seemed to be very little understanding.

And my mother was hugely affected by what was the ripping apart of her home country. She couldn't express it very clearly, but she expressed it in a very emotional way, and I picked up on a lot of that. So, it was harrowing both the first time around while it was actually happening, and again when I was going back into it many years later, writing about it as well as researching the siege. I went and lived in Sarajevo for five months to get a sense of the place, and to interview people who had lived through the siege. As well as interviewing my great uncle, who this story is very closely based on, I also interviewed other people who were still living in Sarajevo, and that was particularly harrowing. It took me quite a long time when I came back to Norwich, where I was living then, to digest all these war stories and fictionalise them. There was quite a long time when I was a bit depressed, and it took about a year to process it all before I could start writing the stories as fiction.

For my next question, I have to be very honest and say that, before I read Black Butterflies, I was very ignorant about the siege of Sarajevo. So, I just wanted to talk about the role that fiction can play as entry points into certain moments of history that perhaps people aren't that aware of for whatever reason. I personally find fiction quite useful for that purpose because some histories are less known, some appear too complicated to understand, and sometimes it can feel quite daunting to jump into a complex historical account. Whereas a fictionalised account can give readers a small glimpse into a historic time through people and emotions, which tends to be an easier entry to empathy. So, I just wondered, seeing as you've done that for me and hopefully lots of other people, were there any books that you read that had that impact on you? That taught you or informed you about a period that you didn't really know much about before?

Yes, good question and that is, by the way, exactly what I was aiming for ¬– to shed some light on Sarajevo and what happened because, as you implied, history books can be very dry and following emotions and a character can be a much more interesting way into the past. For me, there are various books that particularly influenced the writing of this, which I suppose did the same thing. So, for example, there's The Siege by Helen Dunmore which is about the siege of Leningrad. There's also The Plague by Albert Camus, which is interesting because on the surface it's about a plague, much like the one we've just faced with COVID, but it’s also very easy to read it as being about a siege of a city; a lot of people interpret it as an allegory of fascist France, and it can be seen as a book that really throws light on what life is like under a state of siege or a totalitarian regime. I also absolutely love Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient, set at the end of the Second World War in Italy and Northern Africa and focusing on, not the main heroes of the war, but the people who are often overlooked: a nurse, a thief, a sapper. That, for me, is one of my favourite novels, and it was actually quite an inspiration when I was writing Black Butterflies. Some other war fiction that I found inspiring are Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, which does exactly what you talking about and builds a layered, complex understanding of the Nigerian Civil War through compelling characters, the brilliant Milkman by Anna Burns, which evokes the siege-like state of terror and half-truths that people lived in during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, Love and Obstacles by Sarajevan author Aleksandar Hemon, the darkly comic Lodgers by Nenad Veličković, written and set during the siege of Sarajevo, and the truly wonderful Catch the Rabbit by Lana Bastašić, about a surreal female roadtrip through postwar Bosnia.

Were they also inspirational to you stylistically as well? Do you have any authors that particularly influenced your writing style and the way that you write?

I would say that Michael Ondaatje is a favourite of mine, and then there are four authors I really love, which are quite disparate, but they've stayed with me throughout my life, and they would be Alice Walker, Angela Carter, Ali Smith, and Tove Janssen.

Oh, cool!

Bit of a surprise there! Her adult fiction is just written beautifully. I was actually just trying to think what draws all these writers together for me and I think it is the strength and resilience of their female characters; they're very authentic female characters that are non-conventional. They're true to themselves, and there's a power and something to admire in that. And, equally, all of them have a real beauty and simplicity in the prose that is used, it is a visual prose that just really speaks to me. So, I think that somehow, the work of these authors has fed into Black Butterflies, perhaps into the spirit of Zora, who is a strong, resilient, female protagonist.

Definitely! That seamlessly leads me to my next question about Zora who, as well as being a very strong character, is an artist, which was really lovely as I felt like it gave the reader a lovely insight into the beauty of the city in a more artistic way; it gave the book a wonderful element of creativity. I just wanted to ask you more about the decision of making her art speak in the novel.

Yes, so the original inspiration for the story was me hearing my Great Uncle’s story, and he was a landscape painter in Sarajevo whose work burnt down during the siege. When I heard his story, something went off in my head – ‘art, fire, war’ – and this combination was the muse for this story. So, it was very important to me that she's an artist, and I guess it also has something to do with art being a form of resistance. You know, you've got the complete dehumanisation of being under siege; I mean, a siege is a very long, drawn-out form of aggression. It's not just a quick battle, in Sarajevo it ended up going on for almost four years. And one of the aims of a siege is basically to slowly wear down the people who are being besieged. You cut off all the supplies and you beat them down until they give in, so it's very dehumanising; it's stripping away everything you’re used to: power electricity, water, food. So, to carry on creating art is a way of reclaiming your humanity and lifting yourself up – and people really did do this in Sarajevo. It was quite amazing, especially in the second year of the siege, suddenly all this artistic life started flourishing and plays were put on in candlelight theatres and there was music. It was kind of amazing. I very much wanted to explore the theme of art being an antidote, or resistance, to war; it is very much a part of what inspired Black Butterflies.

And similarly, I wanted to ask about the moments of connection and even love and lust that you focus on during the siege; is there a similarity to art there in the sense of reclaiming your essence, your body, your humanity?

Yes, I love that. I hadn't necessarily thought of that myself, but yes there is. The theme of neighbourliness that goes on between Zora and the other neighbours in her tower block is very important; they're all different nationalities, and yet they continue to help each other and get on. And then there's also this love story that goes on between Zora and Mirsad, which again is a form of resistance to war just as you're saying; it’s showing that love and friendship and being neighbourly and all these things continue, despite being shelled. And again, it very much came from stories I heard when I was in Sarajevo – that people really helped each other and looked out for each other, and that love continued to grow even in warlike conditions.

I wonder, and I don't know if you did this on purpose, but I personally found that the way that the book doesn't really apologise, explain, or justify Zora’a relationship – even though Zora is married – made it feel like this relationship is almost necessary for survival.

That's exactly how I intended it. At this point, when Zora and Mirsad do get together, she has pretty much given up all hope of escaping and she feels completely cut off; she doesn't think she's ever going to see her husband again. And you know, when you’re only focused on day-to-day survival, the normal concerns you'd have sort of leave your mind. Partly, they get together for warmth because it’s -20¬ degrees in the flat, but it's more than just that, of course. There's something strong growing between them both, and that's also why – apart from a few hints at her feeling conflicted about it in her actions – there's no explanation and no apology.

Our last question is one that we ask everyone we speak to, so you might have seen it before in our other interviews, but we wanted to know whether you judge a book by its cover?

It's a great question. I happen to love the cover of Black Butterflies, so I would be very happy if people judged this book by its cover. But if the question is, ‘Do you select a book by its cover? Then, certainly, that might be something that draws me to a book, absolutely. Usually, it’s the cover, the title, and the first page that makes me decide whether or not to buy it. But having read a book and loved it, I wouldn’t judge it by its cover, of course.

A very diplomatic answer.